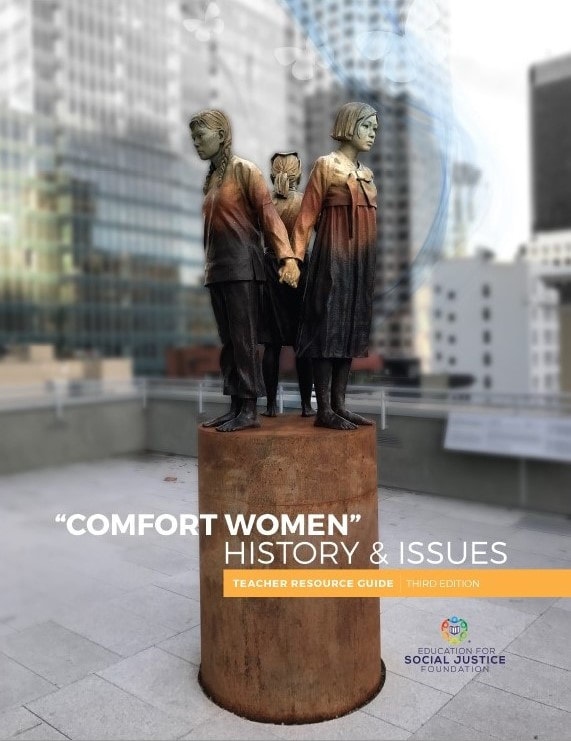

JAPANESE MILITARY SEXUAL SLAVERY SYSTEM

|

Hak-Soon Kim (1924–1997), first survivor of the Jpapanese wartime military sexual slavery system to testify in public on August 14, 1991, speaking at the Wednesday Demonstration in 1996

Photo credit: The Korean Council |

While stationed in China from 1937 to 1940 during the Second Sino-Japanese War, Murase documented the horrors of war through photography. In his book, My China Front (1987), he included close to two hundred photos, voicing his opposition to the war and condemning the atrocities the Japanese government committed against civilians and soldiers.

|

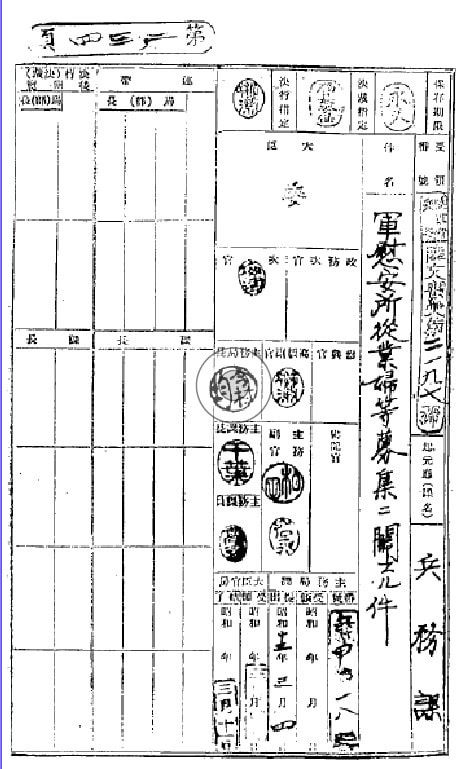

From the 1930s to the end of World War II in 1945, the Japanese Imperial Armed Forces established and operated numerous“comfort stations” for Japanese soldiers in the territories they occupied. Hundreds of thousands of women and girls from throughout Asia were forced into this military sexual slavery. These women and girls are euphemistically referred to as “comfort women.” The UN defines this state-sanctioned and systemic violence as a crime against humanity. Since the ’90s, the survivors have fought for a sincere and official apology from the Japanese government, along with reparations, not charitable compensation.

Teaching “comfort women” history today bears significance. First, this crime continues today, and learning its history can help stop or disrupt the cycle of sexual and gender-based violence (SGBV). Second, the history of “comfort women” is a deeply relevant topic rooted in imperialism, human rights violations, violence, discrimination, as well as distortion and denial of history—fundamental problems that echo into today. The questions raised by the history of and issues surrounding “comfort women” also extend to critical issues of civil rights advocacy, such as the #MeToo movement and the Black Lives Matter movement. Lastly, through the grassroots movement led by the survivors, this history demonstrates the empowering impact of advocacy and civic engagement. It reminds us that we have the power to advocate for ourselves should our rights and dignity be violated or compromised. It also teaches us that we all have a responsibility to advocate for and support others. By leading the grassroots movement for women’s human rights and empowerment, the survivors of the Japanese military sexual slavery system turned what could have been sidelined history into a transnational women’s rights movement.

Teaching “comfort women” history today bears significance. First, this crime continues today, and learning its history can help stop or disrupt the cycle of sexual and gender-based violence (SGBV). Second, the history of “comfort women” is a deeply relevant topic rooted in imperialism, human rights violations, violence, discrimination, as well as distortion and denial of history—fundamental problems that echo into today. The questions raised by the history of and issues surrounding “comfort women” also extend to critical issues of civil rights advocacy, such as the #MeToo movement and the Black Lives Matter movement. Lastly, through the grassroots movement led by the survivors, this history demonstrates the empowering impact of advocacy and civic engagement. It reminds us that we have the power to advocate for ourselves should our rights and dignity be violated or compromised. It also teaches us that we all have a responsibility to advocate for and support others. By leading the grassroots movement for women’s human rights and empowerment, the survivors of the Japanese military sexual slavery system turned what could have been sidelined history into a transnational women’s rights movement.

_______________________________________________________