Historic lawsuits related to Japanese military sexual slavery

I. April 27, 1998: Shimonoseki Branch of the Yamaguchi District Court, Japan

The first time the Japanese Court accepted Japanese military sex slaves’ testimony as reliable evidence and confirmed the establishment and operation of the state-sanctioned military sexual slavery system

In December 1992, Moon-Sook Kim, later chairwoman of the Busan Council for the Women Drafted for Military Sexual Slavery by Japan, led three former “comfort women”—Sun-Dok Lee (1918–2017), Soon-Nyo Ha (1920–2000), and Doo-Ri Park (1924–2006)—and seven survivors of the Female Volunteer Labor Corps to file a lawsuit in the Shimonoseki Branch of the Yamaguchi District Court. On April 27, 1998, while a three-judge panel denied the compensation to forced labor plaintiffs, the Shimonoseki branch of the Yamaguchi Prefectural Court ordered the Japanese government to pay compensation of 300,000 yen (around US$2,400 in 1998) to each of the three Korean “comfort women” plaintiffs.[1] It was the first time that the Japanese Court accepted the testimonies of the former “comfort women” as reliable evidence and confirmed the establishment and operation of the state-sanctioned military sexual slavery system.[2] However, this historic judgment was overturned in the Hiroshima High Court in 2001 and the Supreme Court of Japan in 2003. Moon-Sook Kim said that what she and the survivors want more than anything is a sincere apology, not money, from the Japanese government.[3]

[1] “‘Comfort women’ secure historic courtroom victory,” The Irish Times, April 28, 1998.

[2] Etsuro Totsuka, “Commentary on a Victory for ‘Comfort Women’: Japan’s Judicial Recognition of Military Sexual Slavery,” 8 Pac. Rim L. & Pol’y J. 47, 1999.

[3] Yun, Hyun-Joo. [윤현주의 맛있는 인터뷰] 일본군 위안부 대모 김문숙‘민족과 여성 역사관’관장, Busan.com, Aug. 13, 2019.

II. August 30, 2011: South Korea Constitutional Court

On August 30, 2011, the South Korea Constitutional Court ruled that neglecting the problems of “comfort women” and Korean atomic bomb victims was a state violation of the victims’ basic human rights. This ruling, validating the nation’s active effort for resolving the problem, opened the door not only for the Korean victims of Japanese military sexual slavery, but also for the Korean victims of the atomic bombs and forced labor, to sue the Japanese government for unpaid wages and reparations. Tens of thousands of Koreans died during the Hiroshima and Nagasaki atomic bombings in 1945.

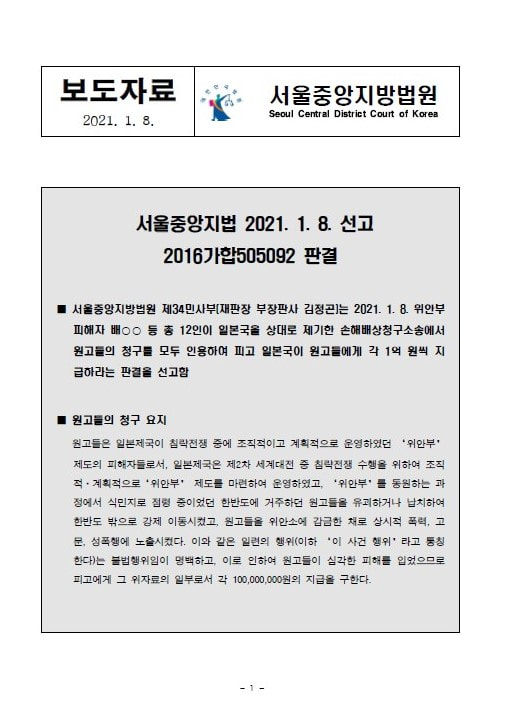

III. January 8, 2021: Seoul Central District Court, South Korea

South Korea court orders Japan to pay reparations to Japanese military sexual slavery victims

On January 8, 2021, the Seoul Central District Court made a landmark decision ordering Japan to pay reparations to the Japanese military sexual slavery system victims before and during World War II. The Court stated that the victims suffered a crime against humanity and ordered the Japanese government to pay 100 million won (approximately US$91,000) each to the surviving victims and family members of those who are deceased. In August 2013, twelve women filed for court mediation seeking 100 million won each for damages incurred from the Japanese government. Japan refused to accept the mediation and relevant documents known as a public notification. Then the case proceeded to a formal trial.

In response to this ruling, Prime Minister Yoshihide Suga said that “Japan cannot accept the court’s ruling.”[1]

Japan has been insisting that the lawsuit should be dismissed on the grounds of state immunity—the state is immune from the jurisdiction of the court of a foreign country. In the ruling, Justice Kim Jeong-gon said that “Even if it was a country’s sovereign act, state immunity cannot be applied as it was committed against our citizens on the Korean peninsula that was illegally occupied by Japan.” He added, “It was a crime against humanity that was systematically, deliberately and extensively committed by Japan in breach of international norms.”[2]

Japan has argued that South Korean individuals do not have the right to claim reparations due to the 1965 agreement between South Korea and Japan. But in 1999, the International Labour Organization formally demanded that the Japanese government provide compensation to forced labor victims and work to provide restitution. Moreover, since the 2000s, international law has strongly trended towards the view that individual claims do not expire as the result of negotiations between countries.[3] In 2018, Seita Yamamoto, an attorney specializing in postwar compensation, recognized this international standard: “The ruling by the Supreme Court of Japan [and the Japanese government] that the South Korea-Japan treaty means that the individual right to make claims exists but claims in court are unacceptable goes against international norms.”[4]

Japan has also repeatedly brought up the 2015 “comfort women” agreement, stating that the agreement was “final and irreversible.” Under this argument, the rights of “comfort women” victims to pursue justice today are nonexistent. However, the 2015 deal, made without the consent of victims who denounce it, was essentially nullified in 2019.

Since this case was brought up in 2013 by twelve Korean victims, euphemistically known as “comfort women,” seven have passed away. One of the deceased victims was Chun-Hui Bae (1923-2014). At the age of nineteen, instead of the factory she was promised to, she was taken to a “comfort station” in Jamuse, China. Her family was too poor to send her to school, where Chun-Hui Bae aspired to go. After she broke her silence, using her savings, she gave scholarships to students in need. She passed away a year after she filed the lawsuit.

Ok-Seon Yi, one of the surviving “comfort women” victims who filed the lawsuit, commented on the ruling as follows: “Japan may wait for all victims to die. Japan must apologize before all victims die.” We hope that she and other surviving victims find some solace in knowing that crimes against humanity have no statute of limitations. At fifteen, Ok-Seon Yi was abducted from her hometown to a “comfort station” at a military airport in East Yanji, China. Ok-Seon Yi also had a strong desire for education, which her family in poverty could not afford. The graphic novel Grass recounts her story. For more of her testimony, click here.

Amnesty International said it was the first time a domestic court had recognized that Japan’s government was accountable for the wartime brothels.[5]

[1] “Suga Calls S. Korea Comfort Women Ruling Unacceptable,” Nippon.com, Jan. 8, 2021.

[2] McCurry, Justin. “Seoul court orders Japan to pay damages over wartime sexual slavery,” The Guardian, Jan.8, 2021.

[3] “Japanese foreign minister acknowledges rights of individual victims of forced labor to make claims,” The Hankyoreh, Nov. 17, 2018.

[4] “[Fact check] S. Korean individuals have the right to claim compensation from Japan,” The Hankyoreh, Aug. 7, 2019.

[5] Kwon, Jen. “South Korean court orders Japan to pay ‘comfort women,’ WWII sex slaves, reparations,” CBS News, Jan. 8, 2021.

Statements:

ESJF (English)

South Korean NGOs (English)

MINBYUN-Lawyers for a Democratic Society (Korean)

The first time the Japanese Court accepted Japanese military sex slaves’ testimony as reliable evidence and confirmed the establishment and operation of the state-sanctioned military sexual slavery system

In December 1992, Moon-Sook Kim, later chairwoman of the Busan Council for the Women Drafted for Military Sexual Slavery by Japan, led three former “comfort women”—Sun-Dok Lee (1918–2017), Soon-Nyo Ha (1920–2000), and Doo-Ri Park (1924–2006)—and seven survivors of the Female Volunteer Labor Corps to file a lawsuit in the Shimonoseki Branch of the Yamaguchi District Court. On April 27, 1998, while a three-judge panel denied the compensation to forced labor plaintiffs, the Shimonoseki branch of the Yamaguchi Prefectural Court ordered the Japanese government to pay compensation of 300,000 yen (around US$2,400 in 1998) to each of the three Korean “comfort women” plaintiffs.[1] It was the first time that the Japanese Court accepted the testimonies of the former “comfort women” as reliable evidence and confirmed the establishment and operation of the state-sanctioned military sexual slavery system.[2] However, this historic judgment was overturned in the Hiroshima High Court in 2001 and the Supreme Court of Japan in 2003. Moon-Sook Kim said that what she and the survivors want more than anything is a sincere apology, not money, from the Japanese government.[3]

[1] “‘Comfort women’ secure historic courtroom victory,” The Irish Times, April 28, 1998.

[2] Etsuro Totsuka, “Commentary on a Victory for ‘Comfort Women’: Japan’s Judicial Recognition of Military Sexual Slavery,” 8 Pac. Rim L. & Pol’y J. 47, 1999.

[3] Yun, Hyun-Joo. [윤현주의 맛있는 인터뷰] 일본군 위안부 대모 김문숙‘민족과 여성 역사관’관장, Busan.com, Aug. 13, 2019.

II. August 30, 2011: South Korea Constitutional Court

On August 30, 2011, the South Korea Constitutional Court ruled that neglecting the problems of “comfort women” and Korean atomic bomb victims was a state violation of the victims’ basic human rights. This ruling, validating the nation’s active effort for resolving the problem, opened the door not only for the Korean victims of Japanese military sexual slavery, but also for the Korean victims of the atomic bombs and forced labor, to sue the Japanese government for unpaid wages and reparations. Tens of thousands of Koreans died during the Hiroshima and Nagasaki atomic bombings in 1945.

III. January 8, 2021: Seoul Central District Court, South Korea

South Korea court orders Japan to pay reparations to Japanese military sexual slavery victims

On January 8, 2021, the Seoul Central District Court made a landmark decision ordering Japan to pay reparations to the Japanese military sexual slavery system victims before and during World War II. The Court stated that the victims suffered a crime against humanity and ordered the Japanese government to pay 100 million won (approximately US$91,000) each to the surviving victims and family members of those who are deceased. In August 2013, twelve women filed for court mediation seeking 100 million won each for damages incurred from the Japanese government. Japan refused to accept the mediation and relevant documents known as a public notification. Then the case proceeded to a formal trial.

In response to this ruling, Prime Minister Yoshihide Suga said that “Japan cannot accept the court’s ruling.”[1]

Japan has been insisting that the lawsuit should be dismissed on the grounds of state immunity—the state is immune from the jurisdiction of the court of a foreign country. In the ruling, Justice Kim Jeong-gon said that “Even if it was a country’s sovereign act, state immunity cannot be applied as it was committed against our citizens on the Korean peninsula that was illegally occupied by Japan.” He added, “It was a crime against humanity that was systematically, deliberately and extensively committed by Japan in breach of international norms.”[2]

Japan has argued that South Korean individuals do not have the right to claim reparations due to the 1965 agreement between South Korea and Japan. But in 1999, the International Labour Organization formally demanded that the Japanese government provide compensation to forced labor victims and work to provide restitution. Moreover, since the 2000s, international law has strongly trended towards the view that individual claims do not expire as the result of negotiations between countries.[3] In 2018, Seita Yamamoto, an attorney specializing in postwar compensation, recognized this international standard: “The ruling by the Supreme Court of Japan [and the Japanese government] that the South Korea-Japan treaty means that the individual right to make claims exists but claims in court are unacceptable goes against international norms.”[4]

Japan has also repeatedly brought up the 2015 “comfort women” agreement, stating that the agreement was “final and irreversible.” Under this argument, the rights of “comfort women” victims to pursue justice today are nonexistent. However, the 2015 deal, made without the consent of victims who denounce it, was essentially nullified in 2019.

Since this case was brought up in 2013 by twelve Korean victims, euphemistically known as “comfort women,” seven have passed away. One of the deceased victims was Chun-Hui Bae (1923-2014). At the age of nineteen, instead of the factory she was promised to, she was taken to a “comfort station” in Jamuse, China. Her family was too poor to send her to school, where Chun-Hui Bae aspired to go. After she broke her silence, using her savings, she gave scholarships to students in need. She passed away a year after she filed the lawsuit.

Ok-Seon Yi, one of the surviving “comfort women” victims who filed the lawsuit, commented on the ruling as follows: “Japan may wait for all victims to die. Japan must apologize before all victims die.” We hope that she and other surviving victims find some solace in knowing that crimes against humanity have no statute of limitations. At fifteen, Ok-Seon Yi was abducted from her hometown to a “comfort station” at a military airport in East Yanji, China. Ok-Seon Yi also had a strong desire for education, which her family in poverty could not afford. The graphic novel Grass recounts her story. For more of her testimony, click here.

Amnesty International said it was the first time a domestic court had recognized that Japan’s government was accountable for the wartime brothels.[5]

[1] “Suga Calls S. Korea Comfort Women Ruling Unacceptable,” Nippon.com, Jan. 8, 2021.

[2] McCurry, Justin. “Seoul court orders Japan to pay damages over wartime sexual slavery,” The Guardian, Jan.8, 2021.

[3] “Japanese foreign minister acknowledges rights of individual victims of forced labor to make claims,” The Hankyoreh, Nov. 17, 2018.

[4] “[Fact check] S. Korean individuals have the right to claim compensation from Japan,” The Hankyoreh, Aug. 7, 2019.

[5] Kwon, Jen. “South Korean court orders Japan to pay ‘comfort women,’ WWII sex slaves, reparations,” CBS News, Jan. 8, 2021.

Statements:

ESJF (English)

South Korean NGOs (English)

MINBYUN-Lawyers for a Democratic Society (Korean)