_______________________________________________________

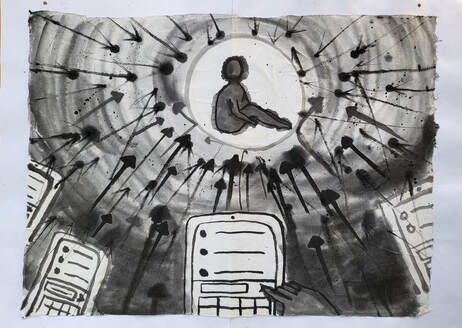

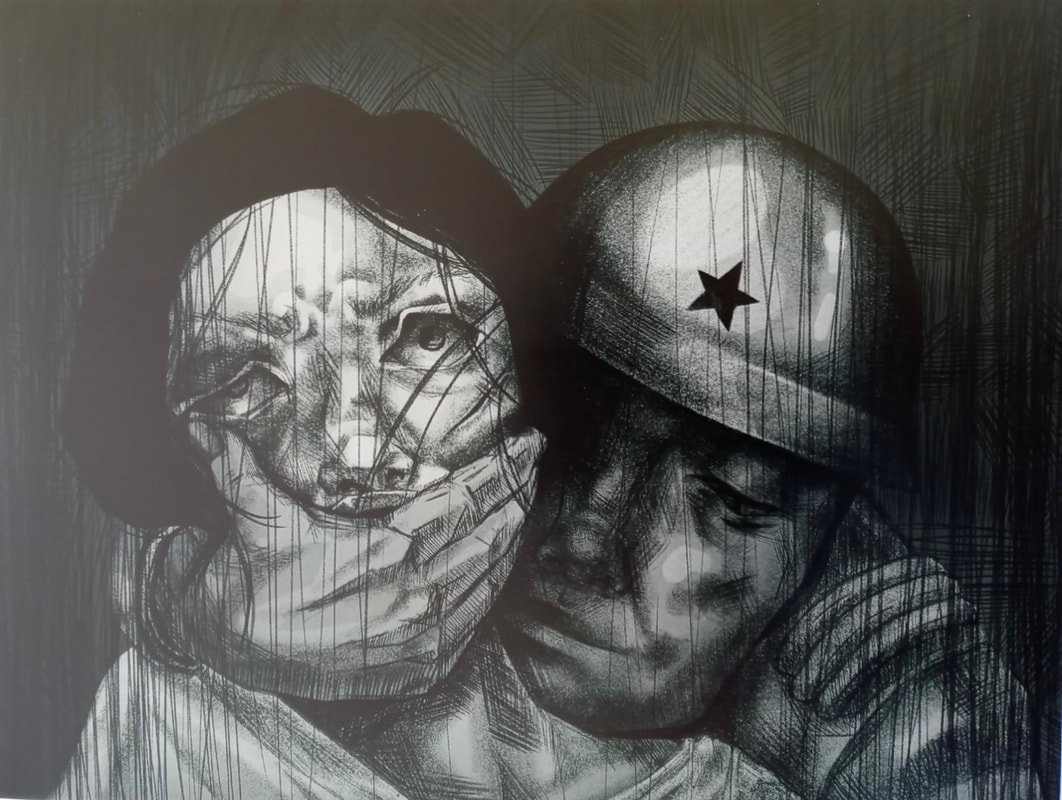

When addressing the significance of peace and countering sexual and gender-based violence, ESJF builds on the lessons learned from the dark history of the Japanese wartime military's sexual slavery system and highlight the progress made by the transnational women's human rights movement in today's intersectional context. We also examine the impact of U.S. foreign policy on the history of redressing Japan’s WWII military sexual slavery system in Asia.

The Japanese military sexual slavery system, established and operated by the Japanese Imperial Armed Forces from the 1930s until the end of World War II, forced hundreds of thousands of women and girls from at least thirteen countries in Asia into military sexual slavery. These women and girls are euphemistically referred to as “comfort women.” The UN defines this state-sanctioned and systemic violence as a crime against humanity.

The Japanese military sexual slavery system, established and operated by the Japanese Imperial Armed Forces from the 1930s until the end of World War II, forced hundreds of thousands of women and girls from at least thirteen countries in Asia into military sexual slavery. These women and girls are euphemistically referred to as “comfort women.” The UN defines this state-sanctioned and systemic violence as a crime against humanity.