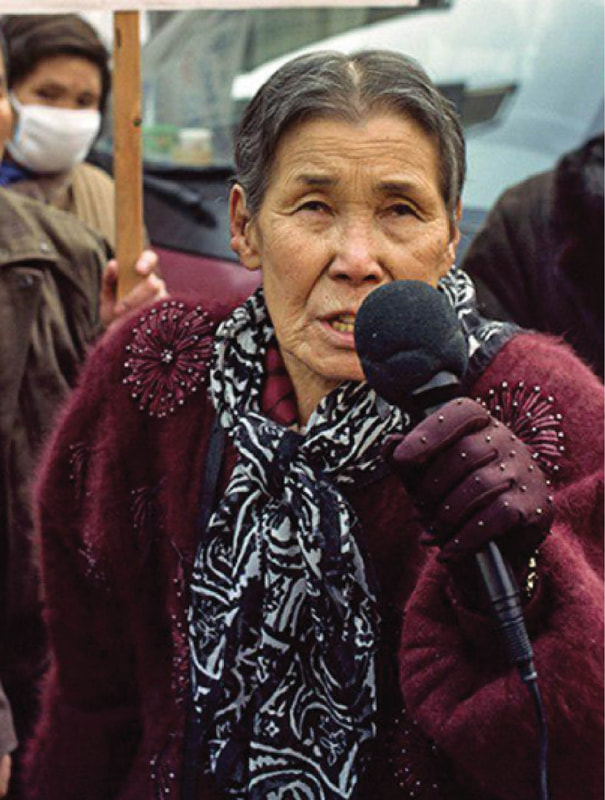

Above Hak-Soon Kim (1924–1997), the first survivor to testify in public on August 14, 1991, speaks at the Wednesday Demonstration in 1996, a weekly protest held in front of the Japanese Embassy in Seoul that amplifies the voices of survivors of the Japanese military sexual slavery system.

Photo credit: The Korean Council (from the exhibition Truth & Justice: Remembering “Comfort Women”)

Photo credit: The Korean Council (from the exhibition Truth & Justice: Remembering “Comfort Women”)

The term “comfort women,” ianfu (慰安婦), is a euphemism referring to women and girls who were forced into state-sanctioned wartime sexual slavery by the Japanese Imperial Armed Forces from the 1930s until the end of World War II. The term “comfort women” is a patriarchal reference, ignoring the inhumanity of systematic sexual and gender violence against young women and girls in Asia. Survivor Jan Ruff-O’Herne (a Dutch-Australian woman born in the Dutch Indies, present-day Indonesia, 1923–2019) disapproved of this term. She said, “We weren’t ‘comfort women’ … it means something warm and soft and cuddly. We were Japanese war rape victims.”

The first known “comfort station” was established in Shanghai in 1932, and after the Second Sino-Japanese War broke out in 1937, the number of comfort stations multiplied. Depending on the degree of control that the Imperial Japanese government had over each of its neighboring countries, women and girls were recruited, coerced, or forced into wartime sexual slavery. This practice violated multiple international conventions, including the following that were established after WWI to counter human trafficking:

1) International Convention for the Suppression of the Traffic in Women and Children (1921);

2) Slavery Convention (1926); and 3) International Labor Organization Convention Concerning Forced Labor or Compulsory Labor (1930):

Among the Japanese soldiers, “comfort women” were considered gifts from the [Japanese] emperor. In his wartime diary, From Shanghai to Shanghai, Aso Tetsuo (served 1937–1941), the first Japanese medical officer ordered to regularly examine the “comfort women” for sexually transmitted diseases, wrote that he noticed that “the women were transported under the clause covering the transport of supplies.” In 1939, Aso recommended that “‘comfort stations’ ... should not be considered amusement facilities, but similar to hygienic, shared toilet.”

During the 1930s and 1940s, instead of the term ‘comfort women,’ the term ‘Female Volunteer Labor Corps’ was widely used. At the conference “Japanese Military ‘Comfort Women’: Remembrance of Post-Colonization and Cultural Re-Actualization” in 2017, Chung-Ok Yun, the first South Korean scholar to expose war crimes committed by the Japanese Imperial Armed Forces against women and girls in Asia, stated, “The majority of Koreans rarely heard or used the term ‘comfort women’ in the ’30s and ’40s.”

These “comfort women,” who were forced into Japanese military sexual slavery against their will and international laws, were deprived of four types of freedoms: freedom of residence, freedom of movement, freedom to decline to have sexual intercourse, and freedom to quit.

Surviving victims testified that, at the end of WWII, the Japanese Imperial Armed Forces either mass murdered “comfort women” or abandoned them. The trauma they experienced didn’t liberate them when Japan surrendered in 1945. For decades, the Japanese government has been masking or denying the history of “comfort women.” In response to this injustice, since the early 1990s, the surviving victims and their supporters in many parts of the world have worked together to bring justice to this sidelined history.

In August 1991, Hak-soon Kim publicly testified to her experience as a former Japanese military sex slave for the first time. A year after, Etsuro Totsuka, an international human rights lawyer from Japan, proposed the use of the term “sex slaves” instead of “comfort women” to the United Nations Commission on Human Rights.

In 2012, during a briefing on the Japanese wartime occupation of Korea, U.S. Secretary of State Hillary Clinton (served 2009–2013) said to a U.S. State Department official who called the victims “comfort women” that the term “comfort women” was inaccurate and “enforced sex

slaves” was more accurate

Activists began calling the victims and survivors of Japan’s WWII military sexual slavery system “grandmothers” rather than referring to them euphemistically as “comfort women.” The girls and young women who were once sex slaves had grown old by the time they broke their silence. The following words mean “grandmother” in different languages in Asian countries mentioned in this guide. The Chinese words for “grandmother” below are terms used by Asian activists in the women’s human rights movement.

China: Daniang 大娘 (Shanxi Province), Apo or Ahpo 阿婆 (Hainan)

Japan: Obaasan おばあさん (formal), Obaachan おばあちゃん (intimate)

Korea: Halmoni, 할머니, Halmae, 할매 (Southern dialect)

Philippines: Lola

Taiwan, Province of China: Ama (Taiwan’s Hokkien Language, Min-nan yu), 阿嬤

Although the term Japanese military sex slaves accurately represents the reality of the victims at military “comfort stations,” because the term “comfort women” has been used widely in official documents and studies for decades, this resource guide uses the terms “comfort women” and Japanese military sex slaves interchangeably. The term “comfort women” is enclosed in quotes to acknowledge its use as a euphemism.

Submitted by Sung Sohn

The first known “comfort station” was established in Shanghai in 1932, and after the Second Sino-Japanese War broke out in 1937, the number of comfort stations multiplied. Depending on the degree of control that the Imperial Japanese government had over each of its neighboring countries, women and girls were recruited, coerced, or forced into wartime sexual slavery. This practice violated multiple international conventions, including the following that were established after WWI to counter human trafficking:

1) International Convention for the Suppression of the Traffic in Women and Children (1921);

2) Slavery Convention (1926); and 3) International Labor Organization Convention Concerning Forced Labor or Compulsory Labor (1930):

Among the Japanese soldiers, “comfort women” were considered gifts from the [Japanese] emperor. In his wartime diary, From Shanghai to Shanghai, Aso Tetsuo (served 1937–1941), the first Japanese medical officer ordered to regularly examine the “comfort women” for sexually transmitted diseases, wrote that he noticed that “the women were transported under the clause covering the transport of supplies.” In 1939, Aso recommended that “‘comfort stations’ ... should not be considered amusement facilities, but similar to hygienic, shared toilet.”

During the 1930s and 1940s, instead of the term ‘comfort women,’ the term ‘Female Volunteer Labor Corps’ was widely used. At the conference “Japanese Military ‘Comfort Women’: Remembrance of Post-Colonization and Cultural Re-Actualization” in 2017, Chung-Ok Yun, the first South Korean scholar to expose war crimes committed by the Japanese Imperial Armed Forces against women and girls in Asia, stated, “The majority of Koreans rarely heard or used the term ‘comfort women’ in the ’30s and ’40s.”

These “comfort women,” who were forced into Japanese military sexual slavery against their will and international laws, were deprived of four types of freedoms: freedom of residence, freedom of movement, freedom to decline to have sexual intercourse, and freedom to quit.

Surviving victims testified that, at the end of WWII, the Japanese Imperial Armed Forces either mass murdered “comfort women” or abandoned them. The trauma they experienced didn’t liberate them when Japan surrendered in 1945. For decades, the Japanese government has been masking or denying the history of “comfort women.” In response to this injustice, since the early 1990s, the surviving victims and their supporters in many parts of the world have worked together to bring justice to this sidelined history.

In August 1991, Hak-soon Kim publicly testified to her experience as a former Japanese military sex slave for the first time. A year after, Etsuro Totsuka, an international human rights lawyer from Japan, proposed the use of the term “sex slaves” instead of “comfort women” to the United Nations Commission on Human Rights.

In 2012, during a briefing on the Japanese wartime occupation of Korea, U.S. Secretary of State Hillary Clinton (served 2009–2013) said to a U.S. State Department official who called the victims “comfort women” that the term “comfort women” was inaccurate and “enforced sex

slaves” was more accurate

Activists began calling the victims and survivors of Japan’s WWII military sexual slavery system “grandmothers” rather than referring to them euphemistically as “comfort women.” The girls and young women who were once sex slaves had grown old by the time they broke their silence. The following words mean “grandmother” in different languages in Asian countries mentioned in this guide. The Chinese words for “grandmother” below are terms used by Asian activists in the women’s human rights movement.

China: Daniang 大娘 (Shanxi Province), Apo or Ahpo 阿婆 (Hainan)

Japan: Obaasan おばあさん (formal), Obaachan おばあちゃん (intimate)

Korea: Halmoni, 할머니, Halmae, 할매 (Southern dialect)

Philippines: Lola

Taiwan, Province of China: Ama (Taiwan’s Hokkien Language, Min-nan yu), 阿嬤

Although the term Japanese military sex slaves accurately represents the reality of the victims at military “comfort stations,” because the term “comfort women” has been used widely in official documents and studies for decades, this resource guide uses the terms “comfort women” and Japanese military sex slaves interchangeably. The term “comfort women” is enclosed in quotes to acknowledge its use as a euphemism.

Submitted by Sung Sohn